Commissioned by the Government Buildings Agency for the customs office on the Maasvlakte (nl)

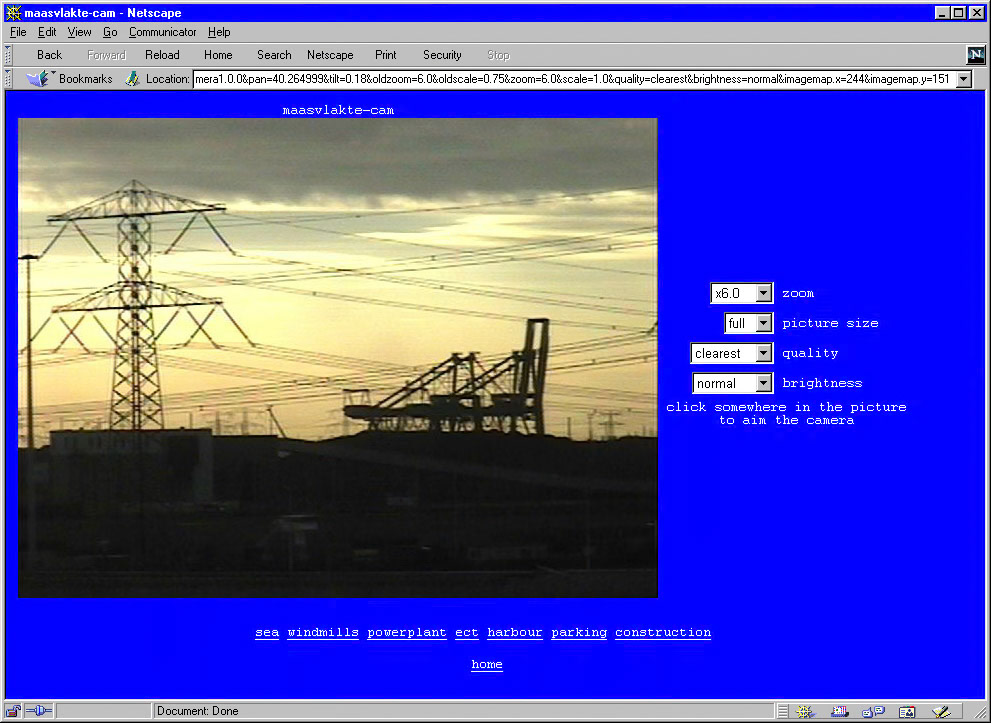

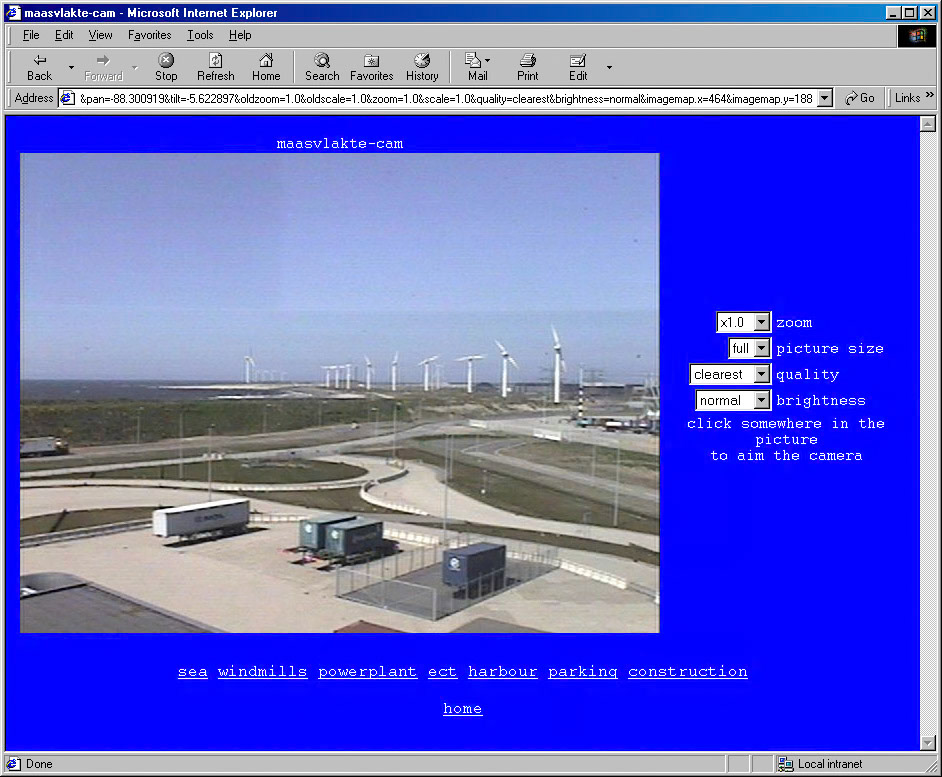

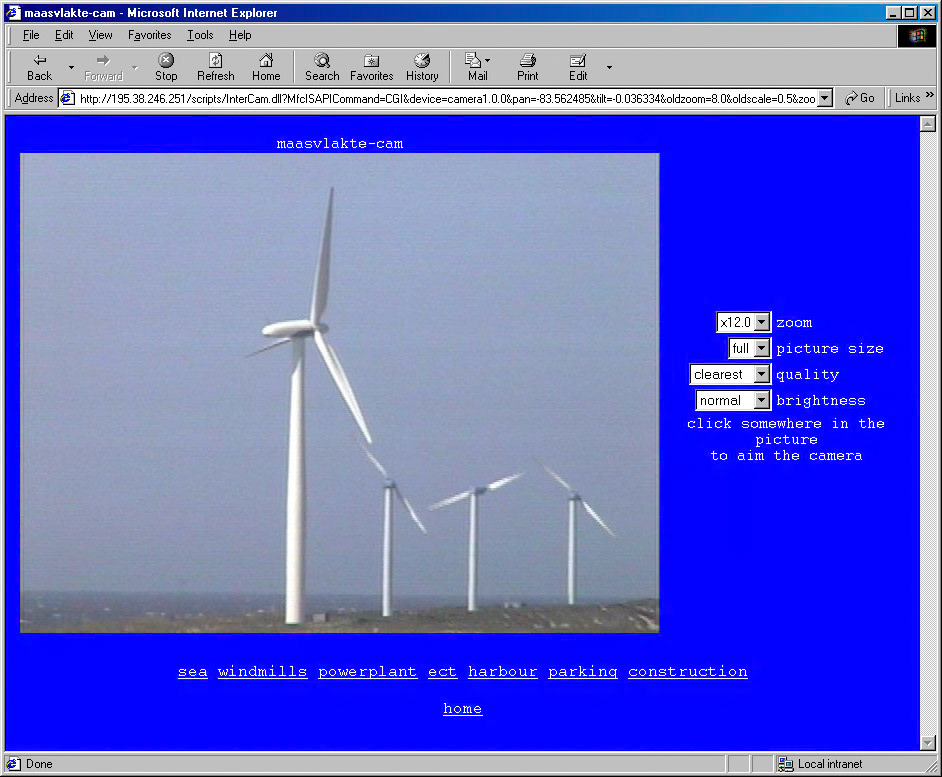

This is a place where goods arrive from all over the world. It is a vast, desolate area with nothing but industrial buildings: an enormous container terminal, a gigantic power plant and huge container ships. There are also crude little beaches all around, adding a totally natural quality to the surroundings. And every-thing is on a scale that defies comprehension. Doorenweerd was interested in webcams at the time. They were still quite rare; it was a really new technology. Looking at a kind of magic lantern on a screen, while conscious of the fact that what he was seeing was actually happening on the other side of the world, intrigued him. The pictures also fascinated him because they were completely devoid of any professional quality. When the customs people came to his studio, he discovered that they were using a similar technology – to scan containers. They also received forms filled in by people from all corners of the earth. This is what prompted him to do something with webcams, and with the idea of ‘the world’. The idea was elaborated in the form of ‘receiving and transmitting’. On the one hand, there were two screens hanging in the building. These screens showed alternating images from a hundred webcams that were set up all over the world and which Doorenweerd had appropriated. Every hour, a hundred of these places passed the viewer’s eye. An hour later they passed by again, but with minor changes, and all this carried on 24 hours a day. Each image was accompanied by a record of its location, date and time. The result was a kaleidoscopic display of mountains, harbors and metropolises, laboratories and squares, border crossings, oceans and cows. You could see that it was snowing in Tokyo, or that the sun was just beginning to rise in Alaska. One of the screens was on the ground floor, where the drivers come in and sit waiting for their containers to be scanned. The other one hung in the canteen upstairs, with a view of the entire Maasvlakte. So besides goods, there were also images coming in from all over the world. The ‘transmission’ part of the project was set up using an interactive camera that was linked to an Internet website and that was mounted on the roof of the container scan. Doorenweerd could operate this camera from his computer at home; but so could other people. Doorenweerd received e-mails from people all over the world who were operating the camera or who had seen the images on the website. They included Dutch emigrants in Canada who were delighted by the opportunity to look around here again. The local surfing club was also very happy, says Doorenweerd, since the camera enabled them to see whether the waves were good on a particular morning. These were all effects he had not anticipated.

The project was to run for three years; this had been agreed beforehand. That is because the connection had to be rented, something that was very expensive at the time. It was also very labour-intensive for Doorenweerd himself, since the technology was still new and often broke down. And then the forces of nature intervened: after three years, a particularly fierce gale swept the camera off the roof. It was hardly surprising, in this rugged open territory. Still, this was not the end of the Maasvlakte-cam. The work had been appreciated so greatly, and was missed so sorely when it stopped, that it was decided to start it up again until a storm blew the camera off the roof. (Elly Stegeman)

The project was to run for three years; this had been agreed beforehand. That is because the connection had to be rented, something that was very expensive at the time. It was also very labour-intensive for Doorenweerd himself, since the technology was still new and often broke down. And then the forces of nature intervened: after three years, a particularly fierce gale swept the camera off the roof. It was hardly surprising, in this rugged open territory. Still, this was not the end of the Maasvlakte-cam. The work had been appreciated so greatly, and was missed so sorely when it stopped, that it was decided to start it up again until a storm blew the camera off the roof. (Elly Stegeman)